What Is the Weight of a New Born Baby Compared to

- Research article

- Open Admission

- Published:

Prevalence of abnormal birth weight and related factors in Northern region, Ghana

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 15, Article number:335 (2015) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Background

Birth weight is a crucial determinant of the development potential of the newborn. Abnormal newborn weights are associated with negative effects on the wellness and survival of the baby and the mother. Therefore, this study was designed to determine the prevalence of abnormal birth weight and related factors in Northern region, Ghana.

Methods

The report was a facility-based cross-sectional survey in five hospitals in Northern region, Ghana. These hospitals were selected based on the unlike socio-economic backgrounds of their clients. The information on birth weight and other factors were derived from infirmary records.

Results

It was observed that depression birth weight is still highly prevalent (29.6 %), while macrosomia (10.5 %) is also increasingly becoming of import. There were marginal differences in low birth weight observed across public hospitals but marked difference in low nascence weight was observed in Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Hospital (Private hospital) as compared to the public hospitals. The private infirmary also had the highest prevalence of macrosomia (20.ane %). Parity (0–i) (p < 0.001), female gender (p < 0.001) and location (rural) (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with decreased risk of macrosomic births. On the other hand, female person infant sexual activity (p < 0.001), residential status (rural) (p < 0.001) and parity (0–1) (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with increased take chances of depression birth weigh.

Conclusions

Our findings show that under nutrition (depression nascency weight) and over nutrition (macrosomia) coexist among infants at birth in Northern region reflecting the double burden of malnutrition phenomenon, which is currently being experienced by developing and transition counties. Both low nascence weight and macrosomia are hazard factors, which could contribute considerably to the electric current and futurity burden of diseases. This may overstretch the already fragile wellness system in Ghana. Therefore, it is prudent to recommend that policies aiming at reducing diet related diseases should focus on addressing malnutrition during pregnancy and early life.

Background

Weight at nativity can be classified into three categories, that is normal (birth weight ≥ii.v kg < 4.0 kg), too light (depression birth weight (birth weight < 2.v kg) or besides heavy (macrosomia) (birth weight ≥ 4.0 kg). The last two weather have adverse consequences on the life of the infant. Studies take shown that autonomously from short-term consequences such as loftier babe mortality and childhood growth failure among survivors, aberrant nativity weight has a long-term risk in the course of high prevalence of adult coronary eye disease and blazon ii diabetes [i]. According to Gluckman [ii], this may be due to fetal or perinatal responses, which may include changes in metabolism, hormone product, and tissue sensitivity to hormones that may hinder the relative evolution of various organs, resulting in persistent changes in physiologic and metabolic homeostatic set points. Low birth weight (LBW) was also shown to have debilitating long-term consequences on childhood development, school accomplishment and adult upper-case letter, including achievement in pinnacle, economical productivity and nativity weight of offspring [3, 4]. Macrosomia is seen as an important gamble gene for prenatal asphyxia, death, and shoulder dystocia, and mothers of babies with macrosomia are at an increased take a chance of caesarean section, prolonged labor, postpartum hemorrhage, and perinatal trauma [5, 6].

Low birth weight is caused by either a short gestation period (<37 weeks) or retarded intrauterine growth (or a combination of both) [7]. Eleven percent (11 %) of all newborns in developing countries are born at term with low nascency weight, a prevalence which is six times more than in adult countries [8, 9]. According to UNICEF [10] the prevalence of low birth weight babies in Ghana is xiii.0 %.

Pre-term birth, maternal age (<20 years and >35 years), stress during pregnancy, maternal under nutrition before pregnancy and outset parity may atomic number 82 to low birth weight [eleven]. Other evidence adduced by Bategeka [12] show that factors such as low socio-economic status and utilize of services such every bit antenatal intendance and tetanus vaccination could influence nativity weight.

On the other manus, macrosomia prevalence in the developed countries is between v % and 20 % but an increase of xv %-25 % has been reported in the by decades, which is solely driven by an ascendance of maternal obesity and diabetes [6]. Notwithstanding, in developing countries information for the changing prevalence of macrosomia are scarce, in one written report in China [thirteen] researchers observed an increment from 6.0 % in 1994 to 7.8 % in 2005. In Ghana, there has been limited report on macrosomia but one recent report [14] reported x.9 % macrosomic births amid obese and overweight women in Bonso specialist hospital in Kumasi, Republic of ghana. As the prevalence of diabetes and obesity in women of reproductive age increase in developing countries [15, 16], a corresponding increase in macrosomic births may exist expected.

High pre-pregnancy weight or BMI, mother's historic period (20-34years) and height, excessive gestational weight gain, gestational and pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, post-term pregnancy and male sexual practice are found to be associated with macrosomia [17–nineteen].

Ghana, like many other developing countries, is experiencing the double burden of malnutrition phenomenon where maternal nether nutrition coexists with maternal over-nutrition [twenty, 21]. This is due to changes in life mode, nutrition, urbanization, and reduced agile commuting to work, utilize of energy saving devices and increasing sedentary employment that create 'obesogenic' environment [22].

Abnormal nascence weight (low nascency weight and macrosomia) may contribute to the current and time to come burden of chronic diseases. Complications during delivery as a result of macrosomia can atomic number 82 to additional hazards to the female parent and newborn in resources scarce settings every bit compared to resource rich settings because of the restricted availability of emergency obstetric and other essential care [23]. Therefore, the present study was aimed at contributing to agreement of the problems related to aberrant birth weight.

The aim of this study was to make up one's mind the prevalence of abnormal birth weight (low birth weight and macrosomia) and related factors such equally socio-economical condition and demographic characteristics of mothers in the Northern region of Ghana.

Methods

The study examined the delivery records of the yr 2013 in five hospitals in Northern Republic of ghana where there has been steady economic growth in the past decade amidst extreme poverty, to decide the prevalence of abnormal nascence weight. Findings from the report will provide useful information to policy makers for the blueprint of appropriate public health interventions. The region is among the poorest regions in the country. The chief occupation of the people in the region is agriculture and related activities. The region has 26 districts, with 24 of them being predominantly rural [24]. This notwithstanding, virtually one-half of the people alive in urban areas with Tamale Metropolis, the regional capital beingness the about urbanized urban center in the region.

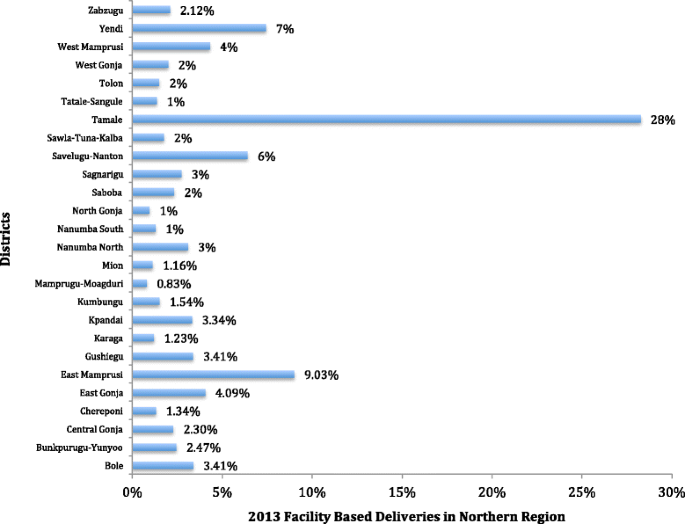

According to UNICEF [10] about 62.seven % deliveries took place in health facilities, just it was observed in one written report that a greater proportion of facility-based deliveries normally occurred in urban areas [25]. As shown in Fig. 1, there are wide variations in the facility-based deliveries beyond districts in the region with three districts – Tamale, Sagnarigu and Savelegu-Nanton bookkeeping for about l % of all the facility-based deliveries in the entire region.

Pattern of facility-based deliveries in Northern Region

Prior to the selection of health facilities for the study, ten key informants (midwives and plan planning, monitory and evaluation officers) who know and sympathise issues related to facility-based deliveries were identified and contacted. The discussion with these cardinal informants was to get their inputs into the pattern and to seek their advice on the selection of the facilities. Their knowledge on the number of facility-based deliveries, availability and abyss of commitment records informed their recommendation. Based on this communication, five hospitals were purposively selected including one of the oldest private facilities in Tamale with the highest number of deliveries, Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Hospital.

The five facilities were located in iii districts, which accounted for about half of all the facility-based deliveries in 2013 in the region (Fig. ane). The hospitals are (1) Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Hospital (CSSH) (2) Tamale Pedagogy Hospital (TTH) (iii) Tamale Central Infirmary (TCH) (4) Tamale Westward Hospital and (TWH) (v) Savelugu District Hospital (SDH). The Hospitals are located in the Tamale Metropolis, Sagnarigu District and Savelugu-Nanton District.

At each facility, the delivery annals for 2013 was obtained and systematic random sampling was used to select individual records with a sampling probability of four. In the case of Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Hospital the number of deliveries was lower than in the public hospitals, so all the deliveries for 2013 were selected. The motherhood records from each of the selected clients was obtained and transcribed onto a data drove form developed and pre-tested at the Yendi Commune Infirmary. For each individual the following information was nerveless; age, parity, nascence weight and Location of the mother. Individual records, which had birth weight missing, were not considered because it was the main dependent variable that was used in the analysis. Too, only singleton deliveries were used.

A low birth weight baby co-ordinate to the world health Organization, is one born with nativity weight <two.5 kg. Macrosomia was defined as nativity weight greater than or equal to 4.0 kg. Therefore, this report considered all birth weights greater than or equal to 4.0 kg as macrosomic births. Birth weight ≥2.5 kg < iv.0 kg was considered normal.

The information was entered using Epi Info version 4.1 and transferred to Stata 12.1 for analysis. Summary statistics were computed to determine the full general prevalence of abnormal birth weight and hateful birth weight in the report population. Statistics were also computed to determine hospital specific prevalence and mean birth weight to assess socio- economic differences and heterogeneity of clients betwixt the hospitals (rural, urban and peri-urban).

Standard of measurement beyond the hospitals was checked past placing a standard weight in the calibration used to measure the newborn weight in all the hospitals; there was no pregnant difference observed in the five hospitals selected for this written report.

A multinomial logistic regression model was used to determine the associations between maternal factors and abnormal birth weight. This model was used because the dependent variable in this written report was nominal (Birth weight: 1 = Depression birth weight, ii = Normal, three = Macrosomia) and the Hausman test performed showed no evidence of violation of the contained of irrelevant alternative (IIA) status. A p-value of less than 0.05 at 95 % confident level was considered every bit statistically significant.

Consistency and plausibility checks were done after the data entry to ensure that errors were reduced. Overall, 0.01 % of the data on birth weight, 0.05 % of the data on parity, 0.03 % of the information on maternal age were missing. Only 1100 (33 %) of the infants had their gestational historic period recorded and for that affair it was non used in the multinomial logistic regression analysis. No attempt was made to input missing data because there was no information about whetehr these information were missing at random [26].

Upstanding approval for the inquiry was obtained from the Navrongo Health Enquiry Centre'south Ethical Review Board and Heidelberg University. Written permission was obtained from the health Hospitals to use the wellness records. Even so, because this written report was done at the population level whereby information were extracted from medical records with no individual identifications, individual informed consent was non obtained.

Results

Characteristics of participating hospitals

The hospitals in this study offer diverse services to clients with varied socio-economic backgrounds. For example, Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Infirmary (Private hospital) provides specialized obstetric and gynecology services to urban and loftier-income class in the Tamale Metropolis.. The clients of Tamale Pedagogy Hospital have mixed socio-economic backgrounds merely are mostly from the high and middle-income classes who are largely urban dwellers. The infirmary also gets clients from the lower income class who mostly come up from the rural areas of the City and through referrals. Tamale Key Hospital as well gets their clients predominantly from the center-income class who are more often than not urban dwellers only a significant proportion also comes from depression-income class.

Tamale West Infirmary provides Obstetric and Gynecology services to mostly the urban poor, some middle-income grade and women from rural Tamale and surrounding districts while Savelugu District Infirmary provides Obstetric and Gynecology services to mostly farming communities and a small proportion of middle-income class and urban dwellers in the District capital. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the selected hospitals.

Nascency weight and related factors

The data was analyzed for 3318 deliveries in 5 hospitals. The mean historic period of the mothers was 27 ± half-dozen years. The mean nascency weight observed among the infants was two.9 ± 0.73 kg. Prevalence of low nascency weight was 29.6 % while the prevalence of macrosomia was 10.94 % (Table 2).

In that location were marginal differences observed in LBW prevalence betwixt the public hospitals just a considerable differences were observed between the public hospitals and the private infirmary ranging from 6.95 % in the Private Hospital to 39.13 % in the Tamale W Hospital (Table 3). All the same, at that place were large differences in the prevalence of macrosomia across all the hospitals ranging from 5.84 % in Tamale Central Hospital to 20.06 % in the Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Hospital (Table 3). The proportion of normal birth weights was 72.99 %, 58.86 %, 72.99 %, l.73 % and 52.33 % in CSSH, TTH, TCH, TWH and SDH respectively.

The risk of infants beingness built-in macrosomic every bit confronting normal in the Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Infirmary (clients are mostly from loftier income course) was 48 % higher as compared to those built-in in the Tamale Education Hospital (clients are more often than not from high and middle income class merely also gets referrals from across the socio-economical strata) whereas in Tamale Central Infirmary (clients are mostly from heart income class) the risk of existence born macrosomic versus normal was 58 % lower relative to Tamale Teaching Hospital when historic period, location and parity of the mother as well as sex of the baby were held constant (Table 4).

On the other hand, the risk of infants being born LBW as against normal in the Cienfuegos Suglo Specialist Infirmary was 79 % lower every bit compared to Tamale Teaching Hospital. In the same vein, the chance of babies beingness born LBW as against normal in Tamale Cardinal Hospital was 37 % lower every bit compared to Tamale Didactics Hospital. However, the chance of babies being born LBW relative to normal in Tamale Westward Hospital (clients are mostly from low and center income form) was 60 % higher compared to Tamale Educational activity Hospital (Tabular array iv).

More to the betoken, the risk of being built-in macrosomic for a first/second born as against normal was 52 % lower compared to a third/fourth born. Too, the gamble of existence born macrosomic as against normal for infants built-in by a rural female parent was 45 % lower compared to an infant born by an urban mother. The risk of being built-in macrosomic as against normal for female infants was besides 37 % lower compared to male infants (Table 5).

Conversely, the run a risk of being born LBW for a beginning/2d built-in relative to normal was 33 % higher compared to a tertiary /quaternary born. In the same vein, the take chances of a female infant being built-in LBW relative to normal was 52 % college compared to a male infant. Moreover, the adventure of a rural woman given birth to a LBW baby as against normal was 2.fifteen times higher compared to an urban woman (Table 5).

Discussion

This written report is the kickoff of its kind in Ghana that examines the prevalence of abnormal nativity weight (low nativity weight and macrosomic births). The findings of the study show that prevalence of low birth weight in Northern Ghana is high as compare to the national prevalence [ten] and about three times college than the WHO'south target of <ten %. These differences were expected since the Northern region is one of the poorest regions in Ghana [27] simply not at this magnitude.

I of the factors that could explicate this observation is that more than of the regions' population is engaged in subsistence farming which is mainly pelting fed simply due to regular drought and erratic rainfall patterns their harvest is not always sufficient to accept them throughout the year. Quaye [28] reported that almost farmer households in the northern region experience significant degree of food insecurity with food insecure periods spanning betwixt 3 and 7 months. As a result in that location is loftier risk of maternal under nutrition in the region [29]. More than so it is observed that there is a higher prevalence of malnutrition in Northern Republic of ghana compared to the South [thirty]. This could be related to the loftier prevalence of depression nativity weight observed in this study.

The high prevalence of LBW observed in the present study could also exist due to poor access to health services such as antenatal services due to socio economic barriers which are found to exist strongly related to access to acceptable prenatal services [12, 31]. About one-half of the population in the region lives in rural areas [24] and for that thing the residents have express access to health services due to the deprived nature of their communities. They as well lack admission to social amenities such as electricity; good roads, potable water and equally a result qualified midwives do not want to have postings in to these communities.

Though information technology must exist said that the government of Republic of ghana has already put measures in place to amend admission to pre-natal services by making antenatal care services free for all pregnant women beyond the nation, the success of these programs is limited due to socio-economic barriers. Other evidence adduced by Betegeka & co. [12] shows that low socio-economic condition and use of services such as antenatal care services and tetanus vaccination could influence birth weight. Therefore, if the government policy were geared towards improving education of the daughter child, which is very low in the Northward [24] as well as access to reproductive wellness and reduction of poverty in the area, it would play a crucial office towards enhancing the newborn nascency weight in Northern Ghana.

The low prevalence of low birth weight in the private hospital was expected because it is obvious that the mothers who deliver in the individual clinics are from high-income class of the social club and have a better socio-economic status as compared to those who deliver in the public hospitals. Better socio-economical condition is institute to take a positive impact on delivery result. It is reported that improved maternal education, income and occupation accept strong positive association with birth weight [32].

High prevalence of macrosomia was as well observed in the present study simply this appeared not to be very unlike from prevalence reported by studies in other developing countries, which used a similar cut-off point as this study especially in Africa. For case, a prevalence of seven.5 %, 8.4 % and 14.9 % was reported in Nigeria, Uganda and People's democratic republic of algeria respectively [19] and in Cathay investigators of one study revealed an increased macrosomic birth from half-dozen.0 % in 1994 to 7.8 % in 2005 [13]. Another study in Port Harcourt in Nigeria shows macrosomia prevalence of 14.65 % [33] and in Ghana a contempo study in one specialist hospital reported a prevalence of 10.ix % [14]. This is a clear manifestation of the double brunt of malnutrition phenomenon, which is increasingly condign a public health problem in developing countries where maternal under-nutrition coexists with maternal over-diet [xx, 21]. Diabetes is believed to be an of import risk factor for macrosomia [19] and could be a contributory factor for the increased prevalence of macrosomic births in Northern Ghana.

The report also confirmed established risk factors of macrosomia. For example, parity 2–3 was associated with increased risk of macrosomic births, which is consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Koyanagi & co. [19]. They showed that parity 2–three or college are associated with increased in odds ratios for macrosomia in developing countries. Abreast this, female person gender was also associated with increased risk of low birth weight, which also conforms to other findings. High risk of low birth weight was observed in infants built-in by mothers residing in rural areas and this was plant to be consistent with findings of other studies. For example, studies conducted in United States [34] constitute high prevalence of low birth weight infants born by mothers in rural counties every bit compared to infants built-in by mothers in urban/large rural counties. The rural differences in nativity weight could be due to a variety of factors such every bit poor access to health services [34–36] and socio-economical differences [37–40].

The report had some limitations considering of irregularities of data in the commitment annals. For example in every infirmary the delivery records were nether the responsibility of the nurse in accuse of the motherhood ward. They were kept in a variety of places and could just be located if the in-charge was present. At that place were difficulties in locating the maternity annals in some facilities. This was because the active maternity register books were kept on the desk-bound in the nursing station and the old one (previous years) kept by the maternity ward in-charge. Tamale Primal Hospital could non provide delivery records for April, May, June, and July while at the Tamale West Hospital, January, Feb and March delivery records could not be plant.

There was wide variation in the level and type of information provided in the maternity records. Some facilities recorded gestational age while others did not. The availability of data varied, ranging from 99.9 % for birth weight to 33 % for gestational historic period at delivery. Equally a result of the absense of gestational age at delivery in the delivery register in some of the hospitals gestational historic period, which is noted as a confounder of birth weight was excluded in the analysis.

Conclusions

Our findings testify that under nutrition (LBW) and over nutrition (macrosomia) coexist amid infants at birth in the Northern region of Republic of ghana reflecting the double brunt of malnutrition phenomenon, which is currently beingness experienced by developing and transition counties. Given the paradox with increased gamble of obesity at both ends of the birth weight spectrum and the potential health risks of low birth weight and macrosomia coupled with the 'obesogenic' environment that is being created by the steady urbanization in developing countries, there is a need for a paradigm shift in the fight confronting nutrition related diseases past focusing on preconception and maternal nutrition during pregnancy in a comprehensive and inclusive manner.

Our findings also provided empirical back up for the link that existed between infant sex activity, maternal age, parity and differences in socio-economical classes and nascency weight.

Abbreviations

- UNICEF:

-

United nations International Children's and Emergency fund

- WHO:

-

Globe Health Organization

- ACOG:

-

American Higher of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

References

-

Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C. Fetal origins of developed disease: forcefulness of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1235–9.

-

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of In Utero and Early-Life Conditions on Adult Health and Illness. N Eng J Med. 2008;359:61–73.

-

Victora CG, Adair Fifty, Autumn C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult wellness and homo capital. Lancet. 2008;371(9609):340–57.

-

Kaiser L, Allen LH. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition and lifestyle for a good for you pregnancy outcome. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(3):553–61.

-

Haram K, Pirhonen J, Bergsjo P, Pirhonen J, Bergsjo P. Suspected big babe: a difficult clinical problem in obstetrics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:185–94.

-

Henriksen T. The macrosomic fetus: a claiming in electric current obstetrics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:134–45.

-

Kramer MS. Determinants of low nascence weight: methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Wellness Org. 1987;65(v):663–737.

-

de Onis M, Blossner Grand, Villar J. Levels and patterns of intrauterine growth retardation in developing countries. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obs. 1998;52:0954–3007. Print.

-

Bergmann RL, Bergmann KE, Dudenhausen JW. Undernutrition and Growth Brake in Pregnancy. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr. 2008;61:103–21.

-

UNICEF. The state of the earth's children. New York, USA: UNICEF; 2013.

-

Isiugo-Abanihe UC, Oke OA. Maternal and ecology factors influencing infant nascency weight in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Popul Stu. 2011;25(ii):250–66.

-

Bategeka L, Leah Yard, Okurut A, Berungi M, Apolot JM. The determinants of nativity weight in Uganda. Nairobi: AERC; 2009.

-

Lu Y, Zhang J, Lu X, Eleven W, Li Z. Secular trends of macrosomia in southeast China, 1994–2005. BMC public health. 2011;xi:818.

-

Addo VN. Body mass index, weight gain during pregnancy and obstetric outcomes. Republic of ghana Med J. 2010;44(2):64–nine.

-

Martorell R, Khan LK, Hughes ML, Grummer-Strawn LM. Obesity in women from developing countries. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:247–52.

-

Roglic K. Diabetes in women: the global perspective. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104(1):S11–13.

-

Chatfield J. ACOG issues guidelines on fetal macrosomia. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Am Fam Doctor. 2001;64:169–70.

-

Yu DM, Zhai FY, Zhao LY, Liu AD, Yu WT, Jia FM, et al. Incidence of fetal macrosomia and influencing factors in China in 2006. Chin J Prevent Med. 2008;16:11–iii.

-

Koyanagi A, Zhang J, Dagvadorj A, Hirayama F, Shibuya K, Souza JP, et al. Macrosomia in 23 developing countries: an assay of a multicountry, facility-based, cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2013;381:476–83.

-

Müller O, Jahn A. Malnutrition and Maternal and Kid Health. In: J East, editor. Maternal and Child Health. NewYork, Dordrecht, Heielberg, London: Springer; 2009. p. 287–310.

-

de-Graft Aikins A. Civilization, diet and the maternal body: Ghanaian women's perspectives on food, fat and childbearing. In: Tremayne Due south, editor. Fatness and the Maternal Body: Women'southward experiences of amount and the shaping of social policy. Oxford: Berghahn Books; 2011. p. 130–54.

-

Popkin BM. Using inquiry on the obesity pandemic as a guide to a unified vision of diet. Public Health Nutr. 2005;viii:724–nine.

-

Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis 50. Prove-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we salvage? Lancet. 2005;365:977–88.

-

Ghana Statistical Service. Population and Housing Demography. Accra, Ghana: Ghana statistical Service; 2010.

-

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Republic of ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF Macro. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Accra, Republic of ghana: GSS, GHS, and ICF Macro; 2009.

-

Trivial RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical assay with missing information. New York: Wiley; 1987.

-

Globe Bank. Tackling Poverty in Northern Republic of ghana. Washington DC, United states of america: World Bank; 2011.

-

Quaye W. Food security situation in northern Ghana, coping strategies and related constraints. African J Agri Res. 2008;3(five):334–42.

-

Laar A, Aryeetey R. Nutrition of women and children: Focus on Ghana and HIV/AIDS. In: Stein N, editor. Public Health Nutrition: Principles and practice in community and global health. U.s.: Michael Brownish; 2014.

-

Mary NA, Brantuo WO, Adu-Afuwuah S, Agyepong E, Attafuah NT, Mash G, et al. Landscape analysis of readiness to accelerate the reduction of maternal and child undernutrition in Ghana. Geneva, Switzerland: UNSCN; 2009.

-

Delvaux T, Buekens P, Godin I, Boutsen One thousand. Barriers to prenatal care in Europe. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:52–9.

-

Khatun Due south, Rahman M. Socio economic determinants of low birth weight in Bangladish: Multivariate Arroyo. Bangladesh Med Res Couns Bull. 2008;34(3):81–6.

-

Ojule JD, Fiebai PO, Okongwu C. Perinatal consequence of macrosomic births in Port Harcourt. Niger J Med. 2010;19(4):436–twoscore.

-

Bailey BA, Cole LK. Rurality and birth outcomes: findings from southern appalachia and the potential function of pregnancy smoking. J Rural Health. 2009;25(ii):141–9.

-

Luo ZC, Kierans WJ, Wilkins R, Liston RM, Mohamed J, Kramer MS. Disparities in birth outcomes by neighborhood income: temporal trends in rural and urban areas, British Columbia. Epidemiol. 2004;15(vi):679–86.

-

Strutz KL, Dozier AM, Van Wijngaarden E, Glantz JC. Birth outcomes beyond three rural–urban typologies in the finger lakes region of New York. J Rural Wellness. 2012;28(ii):162–73.

-

Wingate MS, Bronstein J, Hall RW, Nugent RR, Lowery CL. Quantifying risks of preterm birth in the Arkansas Medicaid population, 2001–2005. J Perinatol. 2012;32(three):176–93.

-

Nagahawatte NT, Goldenberg RL. Poverty, maternal health, and agin pregnancy outcomes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:lxxx–5.

-

Weck RL, Paulose T, Flaws JA. Bear on of ecology factors and poverty on pregnancy outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(ii):349–59.

-

Orr ST, Reiter JP, James SA, Orr CA. Maternal wellness prior to pregnancy and preterm nativity among urban, low-income black women in Baltimore: the Baltimore Preterm Birth Written report. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(1):85–ix.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the managers of the Hospitals where the data drove took place specially the Caput of Obstetric and Gynecology Department of TTH, the manager of CSSH and all the midwives in charge of the labor and maternity wards of TTH, TCH, TWH, CSSH and SDH. Nosotros besides thank the nutrition officers of the above hospitals for their immense support during the data collection. This piece of work would not have been possible without the support of the Dean of School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University for Evolution Studies, Tamale, Republic of ghana.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional data

Competing interests

Nosotros take no competing interest to declare.

Authors' contributions

Conceived and designed the written report: AA AJ. Data analysis and estimation: AA AJ GK-W. Wrote the showtime draft of the manuscript: AA. Contributed to writing: AA AJ GK-W. Have given last approving of the version to be published: AA AJ GK-Due west. Criteria for authorship read and met: AA AJ GK-W. Agreed with manuscript results and conclusion: AA AJ GK-Due west.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you lot requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and signal if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/goose egg/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this article

Cite this article

Abubakari, A., Kynast-Wolf, 1000. & Jahn, A. Prevalence of abnormal nascence weight and related factors in Northern region, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15, 335 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0790-y

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12884-015-0790-y

Keywords

- Birth weight

- Macrosomia

- Low birth weight

- Prevalence and malnutrition

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-015-0790-y

0 Response to "What Is the Weight of a New Born Baby Compared to"

Post a Comment