What Did President Hoover Do to Devise Strategies for Improving the Economy

When it was all over, I one time fabricated a list of New Deal ventures begun during Hoover'due south years as Secretary of Commerce and so as president. . . . The New Deal owed much to what he had begun.1 —FDR advisor Rexford G. Tugwell

Many historians, nigh of the general public, and even many economists call up of Herbert Hoover, the president who preceded Franklin D. Roosevelt, as a defender of laissez-faire economic policy. Co-ordinate to this view, Hoover's dogmatic delivery to pocket-sized authorities led him to stand up by and do nothing while the economic system collapsed in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash. The reality is quite different. Far from beingness a bystander, Hoover actively intervened in the economy, advocating and implementing polices that were quite similar to those that Franklin Roosevelt later implemented. Moreover, many of Hoover's interventions, similar those of his successor, caused the swell depression to be "great"—that is, to last a long time.

Hoover's early on career

Hoover, a very successful mining engineer, thought that the engineer's focus on efficiency could enable regime to play a larger and more than constructive office in the economy. In 1917, he became head of the wartime Food Administration, working to reduce American food consumption. Many Democrats, including FDR, saw him as a potential presidential candidate for their party in the 1920s. For most of the 1920s, Hoover was Secretary of Commerce under Republican Presidents Harding and Coolidge. As Commerce Secretary during the 1920-21 recession, Hoover convened conferences betwixt regime officials and business organisation leaders equally a way to use government to generate "cooperation" rather than individualistic competition. He specially liked using the "cooperation" that was seen during wartime as an example to follow during economic crises. In contrast to Harding'due south more 18-carat commitment to laissez-faire, Hoover began one 1921 conference with a phone call to "practice something" rather than zilch. That briefing ended with a call for more authorities planning to avert futurity depressions, too as using public works as a solution one time they started.ii Pulitzer-Prize winning historian David Kennedy summarized Hoover's work in the 1920-21 recession this manner: "No previous administration had moved so purposefully so creatively in the face of an economical downturn. Hoover had definitively made the indicate that government should not stand by idly when confronted with economical difficulty."3 Harding, and later Coolidge, rejected most of Hoover'due south ideas. This may well explicate why the 1920-21 recession, every bit steep as it was, was fairly short, lasting 18 months.

Interestingly, though, in his function equally Commerce Secretary, Hoover created a new government plan called "Own Your Own Home," which was designed to increment the level of homeownership. Hoover jawboned lenders and the construction industry to devote more than resources to homeownership, and he argued for new rules that would allow federally chartered banks to practice more residential lending. In 1927, Congress complied, and with this government postage of blessing and the resource made bachelor past Federal Reserve expansionary policies through the decade, mortgage lending boomed. Non surprisingly, this program became part of the disaster of the depression, as banking concern failures dried upwardly sources of funds, preventing the frequent refinancing that was common at the time, and loftier unemployment rates fabricated the government-encouraged mortgages unaffordable. The effect was a large increase in foreclosures.four

The Hoover presidency

Hoover did not stand idly past afterwards the depression began. To fight the rapidly worsening depression, Hoover extended the size and telescopic of the federal government in six major areas: (1) federal spending, (2) agronomics, (3) wage policy, (4) immigration, (5) international trade, and (vi) tax policy.

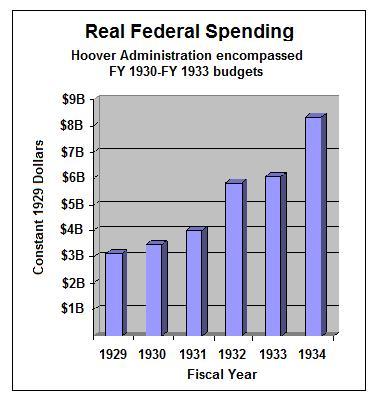

Consider federal regime spending. (Encounter Fiscal Policy.) Federal spending in the 1929 upkeep that Hoover inherited was $3.1 billion. He increased spending to $3.3 billion in 1930, $3.6 billion in 1931, and $4.7 billion and $four.half dozen billion in 1932 and 1933, respectively, a 48% increase over his four years. Because this was a menstruum of deflation, the real increase in regime spending was fifty-fifty larger: The real size of regime spending in 1933 was about double that of 1929.five The budget deficits of 1931 and 1932 were 52.5% and 43.three% of total federal expenditures. No year betwixt 1933 and 1941 under Roosevelt had a arrears that big.6 In curt, Hoover was no defender of "austerity" and "budget cutting."

Effigy 1

Shortly after the stock market crash in October 1929, Hoover extended federal control over agronomics by expanding the reach of the Federal Subcontract Board (FFB), which had been created a few months earlier.7 The idea behind the FFB was to make government-funded loans to subcontract cooperatives and create "stabilization corporations" to keep farm prices upwards and deal with surpluses. In other words, information technology was a dare program. That fall, Hoover pushed the FFB into total activeness, lending to farmers all over the country and otherwise subsidizing farming in an effort to keep prices up. The plan failed miserably, as subsidies encouraged farmers to grow more, exacerbating surpluses and eventually driving prices mode downwards. Equally more than farms faced dire circumstances, Hoover proposed the further anti-market step of paying farmers not to grow.

On wages, Hoover revived the business-government conferences of his fourth dimension at the Department of Commerce past summoning major business concern leaders to the White Business firm several times that fall. He asked them to pledge not to reduce wages in the face up of rising unemployment. Hoover believed, equally did a number of intellectuals at the fourth dimension, that high wages acquired prosperity, even though the true causation is from capital accumulation to increased labor productivity to higher wages. He argued that if major firms cutting wages, workers would not have the purchasing power they needed to buy the goods being produced. Every bit most depressions involve falling prices, cutting wages to match falling prices would have kept purchasing ability abiding. What Hoover wanted amounted to an increase in real wages, as abiding nominal wages would be able to purchase more appurtenances at falling prices. Presumably out of fear of the White Firm or, maybe, because information technology would keep the unions tranquility, industrial leaders agreed to this proposal. The result was speedily escalating unemployment, as firms quickly realized that they could not continue to utilize as many workers when their output prices were falling and labor costs were constant.8

Of all of the authorities failures of the Hoover presidency—excluding the actions of the Federal Reserve between 1929 and 1932, over which he had little to no influence—his endeavour to maintain wages was the most damaging. Had he truly believed in laissez-faire, Hoover would non have intervened in the private sector that way. Hoover'south high-wage policy was a articulate instance of his lack of confidence in the corrective forces of the market place and his willingness to employ governmental power to fight the depression.

Later in his presidency, Hoover did more than only jawbone to proceed wages up. He signed 2 pieces of labor legislation that dramatically increased the part of government in propping up wages and giving monopoly protection to unions. In 1931, he signed the Davis-Salary Act, which mandated that all federally funded or assisted structure projects pay the "prevailing wage" (i.e., the higher up market-clearing union wage). The effect of this motility was to shut out not-union labor, especially immigrants and non-whites, and bulldoze up costs to taxpayers. A twelvemonth later, he signed the Norris-LaGuardia Act, whose 5 major provisions each enshrined special provisions for unions in the law, such as prohibiting judges from using injunctions to stop strikes and making union-free contracts unenforceable in federal courts.9 Hoover'southward interventions into the labor market are further bear witness of his rejection of laissez-faire.

2 other areas that Hoover intervened in aggressively were immigration and international trade. One of the lesser-known policy changes during his presidency was his near halt to clearing through an Executive Guild in September 1930. His argument was that blocking immigration would preserve the jobs and wages of American citizens against competition from low-wage immigrants. Immigration fell to a mere 10 to 15% of the allowable quota of visas for the five-month period ending February 28, 1931. Once again, Hoover was unafraid to arbitrate in the economic decisions of the private sector by preventing the competitive forces of the global labor marketplace from setting wages.ten

Even those with merely a coincidental cognition of the Keen Depression will be familiar with ane of Hoover's major policy mistakes—his promotion and signing of the Smoot-Hawley tariff in 1930. This police increased tariffs significantly on a wide variety of imported appurtenances, creating the highest tariff rates in U.S. history. While economist Douglas Irwin has institute that Smoot-Hawley's effects were non as large every bit oftentimes idea, they still helped cause a decline in international trade, a decline that contributed to the worsening worldwide depression.

Well-nigh of these policies continued and many expanded throughout 1931, with the economic system worsening each month. By the end of the yr, Hoover decided that more drastic action was necessary, and on December eight, he addressed Congress and offered proposals that historian David Kennedy refers to equally "Hoover's second program, " and that has besides been called "The Hoover New Deal."11 His proposals included:

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation to lend revenue enhancement dollars to banks, firms and others institutions in demand.

A Dwelling Loan Bank to provide regime help to the construction sector.

Congressional legalization of Hoover's executive order that had blocked clearing.

Straight loans to state governments for spending on relief for the unemployed.

More assist to Federal State Banks.

Creating a Public Works Administration that would both improve coordinate Federal public works and expand them.

More vigorous enforcement of antitrust laws to stop "destructive competition" in a variety of industries, as well as supporting work-sharing programs that would supposedly reduce unemployment.

On superlative of these spending proposals, most of which were approved in i grade or another, Hoover proposed, and Congress approved, the largest peacetime tax increase in U.Due south. history. The Revenue Act of 1932 increased personal income taxes dramatically, but as well brought back a variety of excise taxes that had been used during World War I. The higher income taxes involved an increment of the standard rate from a range of i.v to 5% to a range of 4 to 8%. On top of that increase, the Act placed a big surtax on college-income earners, leading to a total tax rate of anywhere from 25 to 63%. The Act also raised the corporate income tax along with several taxes on other forms of income and wealth.

Whether or not Hoover'south prescriptions were the right medicine—and the evidence suggests that they were not—his programs were a fairly aggressive use of government to address the problems of the depression.12 These programs were hardly what one would expect from a man devoted to "laissez-faire" and accused of doing nothing while the depression worsened.

The views of contemporaries and modern historians

The myth of Hoover as a defender of laissez-faire persists, despite the fact that his contemporaries clearly understood that he made aggressive use of government to fight the recession. Indeed, Hoover's ain statements made clear that he recognized his aggressive utilise of intervention. The myth also persists in spite of the widespread recognition past modern historians that the Hoover presidency was anything but an era of laissez-faire.

According to Hoover's Secretary of Country, Henry Stimson, Hoover argued that balancing the budget was a error: "The President likened information technology to war times. He said in war times no ane dreamed of balancing the budget. Fortunately we can infringe."13 Hoover himself summarized his administration'southward approach to the depression during a campaign oral communication in 1932:

We might accept done nothing. That would take been utter ruin. Instead, we met the state of affairs with proposals to private business and the Congress of the near gigantic program of economic defence force and counter attack always evolved in the history of the Democracy. These programs, unparalleled in the history of depressions of any country and in any time, to care for distress, to provide employment, to help agriculture, to maintain the financial stability of the country, to safeguard the savings of the people, to protect their homes, are not in the past tense—they are in action. . . . No government in Washington has hitherto considered that it held so wide a responsibility for leadership in such time.14

Some might dismiss this every bit campaign rhetoric, but as the other evidence indicates, Hoover was giving an authentic portrayal of his presidency. Indeed, Hoover'due south profligacy was so articulate that Roosevelt attacked it during the 1932 Presidential campaign.

Roosevelt's own advisors understood that much of what they created during the New Bargain owed its origins to Hoover's policies, going every bit far dorsum as his time at the Commerce Section in the 1920s. Thus the quote at the outset of this commodity by Rex Tugwell, one of the academics at the center of FDR'due south "brains trust." Some other member of the brains trust, Raymond Moley, wrote of that period:

When we all burst into Washington . . . nosotros found every essential thought [of the New Bargain] enacted in the 100-day Congress in the Hoover administration itself. The essentials of the NRA [National Recovery Administration], the PWA [Public Works Administration], the emergency relief setup were all there. Even the AAA [Agricultural Adjustment Act] was known to the Department of Agronomics. Only the TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] and the Securities Act was [sic] fatigued from other sources. The RFC [Reconstruction Finance Corporation], probably the greatest recovery agency, was of course a Hoover measure out, passed long before the inauguration.15

Decades later on, Tugwell, writing to Moley, said of Hoover: "[W]e were too hard on a man who really invented most of the devices we used."16 Members of Roosevelt's inner circumvolve would accept every reason to disassociate themselves from the policies of their predecessor; yet these two men recognized Hoover'southward role as the father of the New Deal quite conspicuously.

Nor is this point lost on contemporary historians. In his authoritative history of the Bang-up Depression era, David Kennedy admiringly wrote that Hoover's 1932 programme of activist policies helped "lay the groundwork for a broader restructuring of government's function in many other sectors of American life, a restructuring known as the New Deal."17 In a after give-and-take of the start of the Roosevelt administration, Kennedy observed (emphasis added):

Roosevelt intended to preside over a government fifty-fifty more vigorously interventionist and directive than Hoover'southward. . . . [I]f Roosevelt had a plan in early on 1933 to upshot economic recovery, information technology was hard to distinguish from many of the measures that Hoover, even if sometimes grudgingly, had already adopted: aid for agriculture, promotion of industrial cooperation, back up for the banks, and a balanced budget. Simply the last was dubious. . . . FDR denounced Hoover's budget deficits.18

Conclusion

Despite overwhelming prove to the opposite, from Hoover's own beliefs to his actions equally president to the observations of his contemporaries and modern historians, the myth of Herbert Hoover's presidency as an example of laissez-faire persists. Of all the presidents up to and including him, Herbert Hoover was ane of the most active interveners in the economic system.

Footnotes

Equally quoted in Amity Shlaes, The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression. New York: Harper Collins, 2007, p. 149.

Murray N. Rothbard, America's Great Depression (1963; Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Found, 2008), p. 192.

David 1000. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. New York: Oxford University Printing, p. 48.

Run across Steven Malanga, "Obsessive Housing Disorder," City Journal, 19 (2), Bound 2009.

Come across the information and discussion in Jonathan Hughes and Louis P. Cain, American Economic History, 7th ed., Boston: Pearson, 2007, p. 487. Hughes and Cain as well annotation of those deficits, "The expenditures were in big part the doing of the outgoing Hoover assistants."

Encounter Kennedy op. cit., pp. 43-44; Rothbard op. cit., p. 228; and Factor Smiley, Rethinking the Great Depression, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002, p. 13.

See Lee Ohanian, "What – or Who – Started the Great Low?" Periodical of Economic Theory 144, 2009, pp. 2310-2335.

Meet "White House Statement on Authorities Policies To Reduce Clearing" March 26, 1931, available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/alphabetize.php?pid=22581#axzz1V7klWwZu. That statement opens with an explicit link betwixt the immigration policy and unemployment: "President Hoover, to protect American workingmen from further competition for positions by new alien immigration during the existing conditions of employment, initiated action last September looking to a cloth reduction in the number of aliens inbound this country."

Kennedy op. cit., p. 83. The phrase "Hoover's New Bargain" is from the title of chapter 11 in Rothbard, op. cit..

Hoover's college revenue enhancement rates backfired, as they further depressed income-earning activity, reducing the tax base, which in turn led to a fall in tax revenues for 1932.

As cited in Kennedy op. cit., p. 79.

Herbert Hoover, "Address Accepting the Republican Presidential Nomination," August 11, 1932.

Raymond Moley, "Reappraising Hoover," Newsweek, June xiv, 1948, p. 100.

Letter from Rexford G. Tugwell to Raymond Moley, Jan 29, 1965, Raymond Moley Papers, "Speeches and Writings," Box 245-49, Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford Academy, Stanford, CA, as cited in Davis W. Houck, "Rhetoric as Currency: Herbert Hoover and the 1929 Stock Market Crash," Rhetoric & Public Diplomacy 3, 2000, p. 174.

Kennedy, op. cit., p. 83.

Kennedy, op. cit., p. 118.

Source: https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/HooversEconomicPolicies.html

0 Response to "What Did President Hoover Do to Devise Strategies for Improving the Economy"

Post a Comment